Chapter 18: C++ Error Handling with Exceptions — The try-catch Mechanism

By Ali Naqi • December 09, 2025

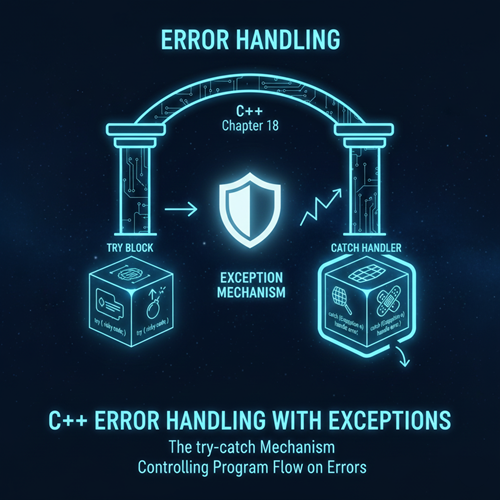

Chapter 18: Error Handling with Exceptions—The try-catch Mechanism

In real-world applications, failures are inevitable: a file might not exist, a network connection might drop, or a mathematical operation might encounter a division by zero. When a function discovers a situation it cannot handle, it must stop its normal process and signal that an error has occurred.

Before C++ adopted exceptions, the standard approach was returning **error codes** (e.g., a function returns -1 on failure). This approach is cumbersome, easily ignored, and makes code messy.

**Exceptions** are the modern, structured C++ mechanism for dealing with run-time errors. They allow you to separate the code that performs the normal work from the code that handles problems.

Section 1: The Three Keywords: try, throw, and catch

C++ exception handling relies on three keywords that define the flow of control:

-

tryBlock: Encloses the code segment that might generate an error. -

throwStatement: Used within thetryblock (or a function called by it) to signal that an error has occurred. Thethrowstatement can throw any data type (an integer, a string, or, preferably, an object). -

catchBlock: Follows thetryblock and contains the code to recover from the exception. It catches the thrown object by type.

Exception Flow of Control

When an exception is thrown:

- Normal execution stops immediately.

- The stack is unwound (local variables in previous functions are destroyed).

- The C++ runtime searches for a matching

catchblock. - If a match is found, the program jumps to the

catchblock, and normal execution resumes from there. - If no match is found, the program terminates (crashes).

#include <iostream>

#include <stdexcept> // For standard exception classes

// Function that might throw an exception

double divide(double numerator, double denominator) {

if (denominator == 0) {

// Throw an exception object (of type std::runtime_error)

throw std::runtime_error("Error: Division by zero attempted.");

}

return numerator / denominator;

}

void demonstrate_exception_handling() {

try {

// Code that might fail goes here (the 'protected' area)

double result = divide(10.0, 2.0);

std::cout << "Result 1: " << result << std::endl;

// This call will throw an exception, and the code below won't run.

result = divide(5.0, 0.0);

std::cout << "This line is skipped." << std::endl;

} catch (const std::runtime_error& e) {

// Code to handle the specific error (e.g., log it, show a message)

std::cerr << "Caught Exception: " << e.what() << std::endl;

} catch (...) {

// Catch-all block for any unhandled exception type

std::cerr << "Caught an unknown exception type." << std::endl;

}

std::cout << "Program continues after the catch block." << std::endl;

}

Section 2: Standard Exceptions and Hierarchies

The C++ Standard Library provides a robust hierarchy of exception classes defined primarily in <stdexcept> and <exception>. All standard exceptions inherit from the base class std::exception.

Common Standard Exceptions:

-

std::bad_alloc: Thrown when dynamic memory allocation (new) fails. -

std::out_of_range: Thrown by STL containers (likestd::vector::at()) when you try to access an index that is too large or too small. -

std::logic_error: Base class for errors that could have been avoided by better programming (e.g.,std::invalid_argument). -

std::runtime_error: Base class for errors that are only detectable at runtime (e.g., I/O errors, system resource failures).

void demonstrate_std_exceptions() {

std::vector<int> v = {1, 2, 3};

try {

// The .at() method throws an exception for out-of-bounds access

v.at(5) = 10;

} catch (const std::out_of_range& e) {

// We catch the specific type of exception

std::cerr << "Vector Error: " << e.what() << std::endl;

}

}

Section 3: Custom Exceptions

You can define your own exception types to signal application-specific errors. The best practice is to inherit from a standard exception class, usually std::runtime_error or std::exception.

class FileNotFoundError : public std::runtime_error {

public:

// Call the base class constructor (std::runtime_error)

FileNotFoundError(const std::string& filename)

: std::runtime_error("File not found: " + filename) {}

};

void load_config(const std::string& filename) {

if (filename != "settings.cfg") {

// Throw our custom exception type

throw FileNotFoundError(filename);

}

// ... file loading logic

}

Section 4: The Critical Link to RAII—Stack Unwinding

The greatest benefit of C++ exceptions is their compatibility with the **RAII** principle (Resource Acquisition Is Initialization, Chapter 14).

When a throw occurs, the C++ runtime performs **Stack Unwinding**. As the program searches up the call stack for a matching catch block, it automatically calls the **destructors** for all local objects in every function it exits.

This means if you use RAII objects (like std::ofstream, which closes a file in its destructor, or a smart pointer, which frees memory), those objects will always clean up their resources, **even if an exception interrupts normal execution**. This makes C++ exception handling extremely safe and prevents leaks.

RAII + Exceptions = No Leaks

The RAII technique (using destructors for cleanup) ensures resource safety during exception handling. This is why C++ discourages manual memory management (new/delete) and strongly favors smart pointers and containers, which are inherently RAII-compliant.

Chapter 18 Conclusion and Next Steps

You have learned the mechanism for robust error handling in C++ using the try, throw, and catch keywords. By employing standard exception hierarchies and creating custom exceptions, you can write reliable code that gracefully handles unexpected failures.

We mentioned that the RAII principle is critical for leak prevention, especially in the context of exceptions. However, manually managing raw memory pointers and exception safety is tedious.

In **Chapter 19**, we will explore the C++ Standard Library's answer to memory management safety: **Smart Pointers**. You will learn how to use std::unique_ptr and std::shared_ptr to automatically manage dynamic memory, making your code safer and simpler.